Table of Contents

7,000 BC

• The West Asia and Caspian Sea areas contain evidence that goats and sheep were sheared for wool and the material was woven. Nomad tribes weaved together rugs to warm earthen floors.

4,000 BC

• Weaved craft is used for Egyptian and Mesopotamian burials, as found in tombs.

2,000 BC

• Other evidence collected by historians indicates the weaving of pile rugs was present in the Middle East and central, northwest, and eastern parts of Asia.

• Carpet-weaving is a part of Persian art and culture in Bronze Age.

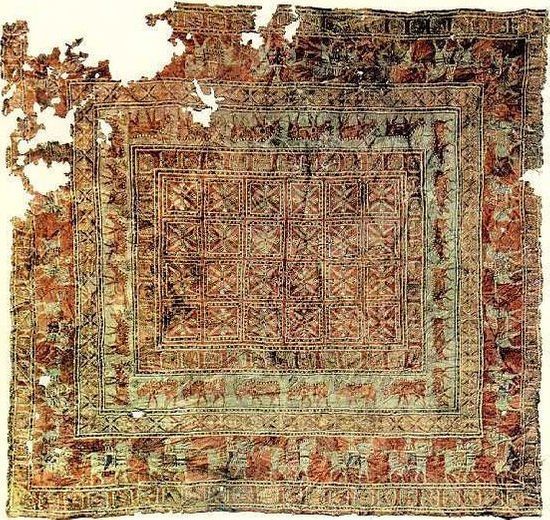

400-500 BC

• The Pazyryk Carpet, the oldest known hand-knotted carpet, is thought to have been made at this time. A Russian anthropologist and archaeologist, Sergei Rudenko, excavated the 300 knots per inch, richly colored carpet in 1949. It was found in a frozen Scythian tomb in Siberia while Rudenko explored the Kurgans in the Altai Mountains. This is the oldest Persian rug known, it is on display in the St. Petersburg Museum.

550 BC

• The Spring Carpet of Chosroes (or Khosrows) that belonged to the King of Persia is made at this time. It is also the second oldest known rug made of wool, silk, gold, silver, and precious stones that weigh up to a few tons. Chosroes is 400 ft x 100 ft in size and depicts beautiful scenes of springtime. When the Arabs conquered Persia, this rug was ripped into many pieces in order to obtain the precious jewels that were woven into the rug.

224-651 AD

• In the text of the Chinese Sui Annals (AD 590-617), Neo-Persian (Sassanid) Empire, the last Iranian empire that ruled Middle Persia before the rise of Islam carries woven products.

13th -14th Century

• The Crusades use and distribute pile rugs in Europe.

• Eleanor of Castile marries Edward I of England in 1254 and brings many fine rugs from her homeland in Spain.

• King Louis IX (1214-1270) spreads rug popularity through France.

• The travel of Marco Polo, an Italian merchant, in the 1260s spreads the influence from the embassies of Venice to China.

15th Century

• Oriental rugs are a symbol of wealth in Europe as noblemen and women have their portraits painted with their Ottoman or Turkish rugs in the background.

• A rug is drawn in San Marco Altarpiece (1438-1443), a painting of the Virgin and Child by Fra Angelico, an Italian painter during the Renaissance.

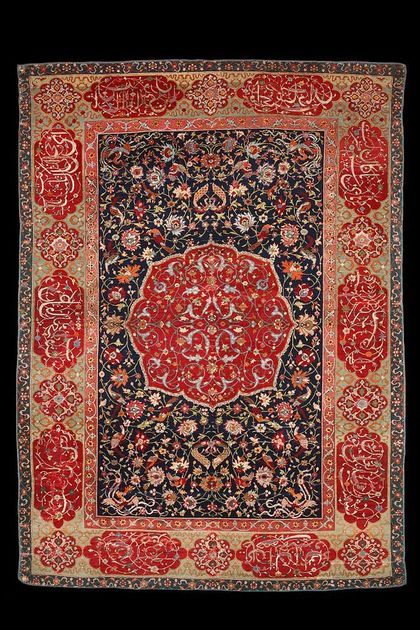

16th Century

• Rug making in China begins during Qing Dynasty and in the Middle East during the reign of the Safavid Dynasty.

• The Ardabil Carpet, encrusted with jewels, is a pair of famous Iranian carpets completed in 1539-40. The foundation of the carpets is made of silk and wool at a density of 300-350 knots per square inch. The size of both carpets is 34.5 ft x 17.5 ft. They were first placed in a mosque in the city of Ardabil and then were sold in England in 1890s. They now reside in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

• The art of rug and carpet making is introduced to India by the great Mughal Emperor Akbar as he brings in Persian weavers from Kashan, Isfahan and Kerman. The Indian carpets are famous because of their detailed designs and high density of knotting.

17th Century

• In 1608, Henry IV (Henry the Great) commissions DuPont and his apprentice Simon Lourdes to produce carpets from a workshop in the Louvre and later in Savonnerie.

• Most residences in England, including palaces and large houses belonging to landowners, made use of rushes and hay strewn about to cover their floors until this time. Over the years, more and more British people of wealth start using pile rugs in their homes.

18th Century

• Native Americans, the Navajos in particular, learn the craft of rug making from the Pueblo tribe. This theory is supported by tribal elders and remnants of Navajo rugs in the 1700s that are a close parallel to rugs made by the Pueblos.

• The Persian rug-weaving industry becomes nearly obsolete in 1722 when the Afghans invade Persia.

19th-20th Century

• British rules the Indian subcontinent in 1858. Gandhi promotes the idea of Khaddar to boycott English clothes. The term Khaddar (Khādī) represents handspun and woven clothes made from a spinning wheel called charkha, and was commonly used in India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan.

• Some of the European countries, especially Belgium, develop a major machine-made rug industry. Rug makers start using synthetic dyes for coloring wool. Workers are paid by the hour instead of by the rug. The worldwide production makes rugs a commonly owned household item.

Rugs can be made of almost any thread made of a type of fiber, natural or synthetic. However, the primary fibers are the natural fibers of wool as a face yarn, and cotton as the foundation fiber. The fiber’s diameter dictates how fine a yarn can be spun. Carpet yarns are rarely spun at the limit of fineness as the coarser the wool, the more durable the rug will be. New Zealand carpet wool has a fiber diameter of 33-37 microns. Middle Eastern rugs are typically made from a combination of short, fine and crimpy wool with medullated (hollow, core-like structure within the fiber) coarse fibers ranging in diameter from 40-62 microns. The fiber’s length is determined by the time taken between instances of the sheep’s shearing. Sheep are typically sheared twice a year or three times over the course of two years. The fiber’s strength is measured in relation to its length and wool is favored for its strength and resilience.

Yarn bulk is typically determined by the fiber’s crimp. Fibers can be blended to achieve the desired level of bulk in the yarn. The natural crimp in wool allows it to absorb noise; that is, the crimp traps air between the fibers. This trapped air provides insulation and increases the fiber’s durability. Wool has moderate abrasion resilience, making it ideal in high-traffic areas. One of the desirable features of wool fiber is that it can absorb up to 30% of its weight in water and still actually feel dry. Because of this feature, combined with the ability to emit heat when absorbing water vapor, wool has a natural ability to blend with the surrounding moisture conditions. In contrast, wool does not absorb oils well, so a wool carpet releases oily residues during the cleaning process.

Weathering the damaging effects of cigarette burns, fireplace embers, and other flames shows the durability of wool. Because of its high moisture and nitrogen content, wool simply chars at the surface and extinguishes itself. This leaves an ash that can typically be brushed away. While they are resilient to some damaging effects, wool fibers are sensitive to sun and UV light, which can cause photo bleaching. Certain chemicals, such as heavy alkaline cleaning solutions, can damage the fibers and cause dye loss. Mechanical action, such as aggressively rubbing a carpet, can lead to felting. Felting occurs when the fibers lock together, or mat, in an irreversible tangle. Combining mechanical action with common cleaning materials such as soaps, moisture, and lubricants accelerates the felting process, damaging the wool irrevocably. This is one of the major reasons that it is important to have your rug cleaned by an educated professional with experience in caring for these precious items, such as Heriz Fine Antique Persian Rugs.

The quality of the wool used in making carpets can be equated to the importance of the quality of wood used in making furniture. Certain qualities to consider are the wool’s resilience, luster, and absorption. The resilience of the wool affects how well it will withstand abrasion throughout its life. The luster is subtle but affects the overall look of the rug, and its absorption factor affects how well it will soak up the dye colors used. All of these factors depend completely on the quality of the wool.

Traditional carpet wool comes from mountain sheep, typically from sheep in India, China, Spain and Wales, though today, sheep in New Zealand produce wool that is best for general carpet manufacturing. Wool from merino sheep is used exclusively for textiles. One merino sheep can produce nearly 5,500 miles of wool fibers in a single year.

Mohair is a natural fiber from the Angora goat. These goats are native of Asia Minor. Smoother than wool, mohair is translucent, springy and lustrous, and is typically not used as a carpet face material in an oriental rug. It is more commonly used, when blended with wool, in making plus upholstery material.

Cashmere is a delicate, expensive natural fiber from the fine downy hair of the Kashmir goat. These goats are native to the Himalayas, India and China. Because of its cost and fineness, it is not used in rugs.

Goat Hair is typically seen in on the sides and warps of tribal and nomadic carpets due to its extremely coarse and scratchy texture.

Camel Hair is similar to cashmere. It is from the downy under-hair of the camel. When combined with other hair, it is seen as a luxury fabric and not typically used in rug production.

Silk is known for luxury. It has been used in tapestries, rugs, fine fabrics, and other accessories for over 4,000 years. In that time, sericulture, the cultivation of silkworms for silk, has remained virtually unchanged. Discovered in China in 2600 B.C., silks eventually made their way to Greece and Rome. Though China tried to protect the process of making silk from the outside world, it eventually spread to Japan and India in the 3rd and 4th century A.D., respectively. It is a well-known credit that Marco Polo, the famous Italian merchant traveler, introduced silk production to Venice. Silk has three unique properties:

Hydroscopicity is the ability to absorb water without feeling wet. Silk can hold up to 30% of its dry weight in water.

Low Specific Gravity means that silk has a low density. The molecular structure of silk looks like a long string of ladders, and in between the “rungs” is air space. This space acts as insulation and allows the silk fiber to breathe.

Strength-in-Fineness means that silk is exceptionally strong. Because of its fineness, silk can be used to weave fabrics and rugs with up to 3,000 knots per square inch! Silk is stronger than any other natural fiber with equal diameter, including nylon and steel wire. Silk does not weaken when wet, though it will show wear through abrasion. Because of this, silk is not the ideal fabric for rugs that will be used on the floor.

Cotton is a seed hair fiber from the cotton plant. Cotton is a very durable fiber, having a high tensile strength and resistance to abrasion. It also effectively absorbs dyes. Cotton resists soil, absorbs moisture and increases its strength when wet. Because of its strength and durability, cotton is a common fiber to use as the foundation for many rugs.

The fiber is most often spun into yarn or thread for its soft, breathable textile. Cotton has been used for thousands of years. The oldest fragments of cotton fabric were dated from 5000 BC in Mexico and Pakistan and some parts of India. With the technology advancement and mass production, cotton continues worldwide, and it is the most widely used in clothing today.

Understanding colors and how they interact with each other is important knowledge for professional rug cleaning technicians. This is another reason that it is imperative to have your rug cared for by professionals. Every color that we see is light that has either been reflected or transmitted by a colorant, such as a pigment or dye.

The use of dye has been dated as early as 2,600 BC in Asia and it was slowly introduced in Rome and other western country around 715 BC. The use and method of dyes is still changing and continuing in the world today.

Acid dyes are anionic and water-soluble. In addition, they are very common in acrylic fiber that has a stronger dye-resistance, silk or nylon for example. Basic dyes are cationic and water-soluble. They are applied with neutral dye-bath at a boiling point for softer material such as wool or cotton.

Other water-insoluble dyes are ground in the presence of a dispersing agent, which is then spray-dried on the fiber.

Natural Dye vs. Synthetic Dye is an old debate as to which is the better system, natural dyes have the reputation of aging with beauty and grace. Natural dyes are often derived from plant material: indigo (blue); madder (red); marigolds (yellow); and from cochineal insect (red). The secondary colors are often made by using two different dyes of primary colors. The color green is formed by over-dyeing the yarn with indigo after it has been dyed yellow.

The dyer is an artisan and there is always a mystery surrounding the exact formulas and methods that they used to obtain the colors in the rug that you're looking at.

Knot Count

Knot count is typically counted in knots per square inch (kpsi) or knots per square meter (kpsm). Think of knot count and rug as pixels and TV in the modern days. Loosely woven rugs can have as few as 16 kpsi and finely woven rugs over 1,000 kpsi. The higher knot count, the more clear and detail the rugs can be. Knot count is one of the factors in determining the value of a rug, next to age, material and origin. In addition, it also deters if the warps are depressed or non-depressed. To explain, a knot has a certain amount of node on each vertical line that are visible on the backside of the rug; if only one node shows, it’s depressed, and non-depressed if two.

Also known as false knots, they are tied around four warps instead of the normal two. A rug made with jufti knots uses less of the material and takes less time to make; on the downside, the rug made with jufti knots will not last as long!

It is common with some rug types, such as BOKHARAS, Tekke-faced rugs. Tekke was a tribe from the area of Bokhara in Central Asia. The design is dominated by rows of guls and surrounding geometric patterns. A gul, a motif on oriental rugs, is a large octagonal design derived from the shape of a rose.

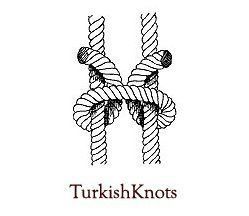

Also known as the Ghiordes knot, the symmetrical design is used in Turkey, the Caucasus, East Turkmenistan, and some Kurdish areas of Iran. To make a Turkish knot, the yarn is passed between two adjacent warps, brought back under one, wrapped around both forming a collar, then pulled through the center so that both ends emerge between the warps.

This type of knot is also known as the Senneh knot as it was named after a Persian city. It is used for finer rugs and is very common in Iran, India, Turkey, Pakistan, China and Egypt. The yarn is wrapped around only one warp, and then passed behind the adjacent warp so that it divides the two ends of the yarn. The Persian knot may open on the left or the right, and rugs woven with this knot are generally more accurate and symmetrical.

The Spanish knot looped around single alternate warps so the ends are brought out on either side while the Jufti knot is tied around four warps instead. It was used mainly in Spain, differs from the Turkish and Persian knot in looping around only one warp yarn. After the 18th century it became extremely rare.

The endless knot - or eternal knot - is a symbolic knot of the Eight Auspicious Symbols— sacred signs endemic to Buddhism, Jainism, and Hinduism. It is an important cultural marker in places significantly influenced by Tibetan Buddhism in Tibet, Mongolia, Tuva, Kalmykia, and Buryatia. It is also sometimes found in Chinese weaving. This knot has a different formation with a temporary rod that establishes the length of pile in front of the warp. Then, a continuous yarn is looped around two warps and then once around the rod. After the yarn went through with the row, the loops are cut to form the knot.

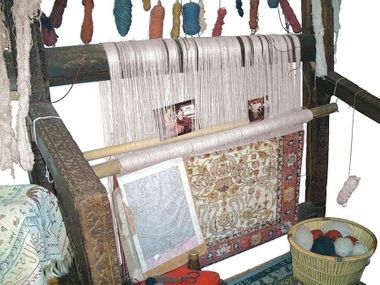

The major components of the loom are the heddle frame, heald, harnesses (shafts in two or four), shuttle, reed and takeup roll. In the loom, yarn processing includes shedding, picking, and battening.

Looms are generally known as either vertical or horizontal. Horizontal looms are easier to dismantle, thus popular in the weaving of tribal rugs. Vertical looms are used in commercial, city and village weaving. There are many different types of looms with several of shapes and mechanics, but the basic purpose is to hold the threads under tension to facilitate the interweaving of threads.

1. Shedding is the raising of part of the warp yarn to form a shed, which is the vertical gap between the raised and the unraised wrap yarns. The heddle frame is a rectangular frame of the loom to which a series wires with harnesses attached.

2. Picking is when a single thread of the weft crosses the warp over and over to fill up the gap. In North America, the process of a “pick” is referred to as “filling yarn.” A weft is threaded through the warp using a "shuttle." During the Industrial Revolution, John Kay’s "flying shuttle," also known as the “wheeled shuttle,” accelerated the production of cloth. Not only did it allow a single weaver to weave wider fabrics, but it can also be mechanized in automatic machine looms. It became possible to make cotton yarn of sufficient strength to be used as the warp in mechanized weaving. Later, artificial or man-made fibers such as nylon or rayon were employed. The power loom patented by Edmund Cartwright in 1785 allowed sixty picks per minute.

3. Battening is the process of pressing down the weft after the shuttle move across the loom. The portion of the fabric that has already been formed but not yet rolled up on the takeup roll is called the fell.

Once a rug is finished, it is then taken off the loom. The sides may be overcast and the ends secured.

The finishing process consists of:

1. Dusting

2. Some rugs are singed on the back with a propane torch to remove fuzzing

3. Chemical wash, rinse and dry

4. Some rugs are blocked

5. Shearing of the front of the rug

6. Quality control check

7. Ready to ship

The three most-used fibers in hand-knotted rugs are wool, silk and cotton. Wool is used as a face yarn and in the foundations (warps and wefts.) Cotton has been used in the foundations of hand-knotted rugs since at least 17th century Prussia, and maybe even before. Silk is used in the pile and in the foundation of some oriental rugs. Silk is also used to outline designs on wool pile rugs.

In weaving, the warp is the set of lengthwise yarns that are held in tension on a frame or loom. A warp is the lengthwise or longitudinal thread in a roll, while weft is the transverse thread. The weft, or sometimes woof, is the term for the thread made of spun fiber that is drawn through the warp yarns to create cloth.

Because the weft does not have to be stretched on a loom in the way that the warp is, it can generally be less strong. On the other hand, warp yarn must be strong to endure the tension.

Bold, geometric patterns with a large medallion in the middle of the carpet are common characteristics of Heriz rugs, as are the vivid colors of rust reds and deep blues. Floral patterns are also found on Heriz antique rugs. Rugs with these patterns are known for their red, blue, yellow, ivory, and green colors.

A cartoon, a design drawn on graph paper with each colored square representing a knot, determines the design of each hand-knotted rug. Designs are also determined by a weaver who chants the design pattern or from the weaver's memory. The cartoon is fixed to the loom just above the eye level of the weaver.

The bottom of a rug is the end on which the first row of knots is tied, and the top of the rug is the end where the last row of knots is tied. The two loose ends of each knot make up the rug’s pile. When the knots are tied, the weaver pulls the ends downward, thus producing the pile’s direction.

Oriental rugs are hand-knotted on a foundation of warps and wefts most often made of wool, cotton or silk. The construction of an oriental rug begins with warp yarns being wrapped around the upper and lower ends of the loom, running the length of the rug and forming the fringe on the top and bottom of the rug. With only a few exceptions, knots are tied around two warps and then trimmed with a small knife. Depressing a warp, that is offsetting it on two different levels, allows for more knots per square inch, creating curvilinear lines and more complex designs. The last warps on each side of the rug are called terminal warps.

The wefts are horizontal yarns woven over and under the warp yarn. This combination is called the foundation of the hand-knotted rug. After one row of knots and wefts has been inserted, the wefts are pounded using a heavy comb; this process adds to the density and rigidity of the rug. The number of wefts between each row of knots, the materials used in the construction and the colors of the wefts all help determine a rug’s origin.

Ends of the rugs must be finished to keep the rug from unraveling after the warps are cut before being taken off the loom. Different rug types are finished in different ways, and this is another component of identification. The edge formed by finishing a side is called a selvage. The end finishes of a rug are not necessarily the same on each end. Furthermore, the side finishes can also vary and are another component of identification. Both finishes are crucial to maintain the beauty and durability of the rug.

The warps are cut when a rug is finished and needs to be taken off a loom. Fringes are the remaining threads from each weft; the fringes can be left cut or uncut depending on the weaver. Some fringes are secured with a cotton kilim or a woven band chain stitched at the last row of knots. Sometimes the weavers make their fringes into braids and saddlebags, and even weave their fringes into more knots with or without a band or kilim.

The sides can be either single or multi-colored finish, the side of the carpet, also known as the edge, is called a selvage. If the weaver decides to not add a tassel or braids, the terminal wraps are returned and loop around the edge weft to make a new row. The edge weft, known as the structural weft, is thicker and more durable than any other wefts, and will increase in size depending on the amount of times that a warp is looped around the weft before turning back to form a new row. Sometimes a terminal warp can be looped around multiple edge wefts to increase stability.

The two basic knots in oriental rugs are the symmetrical Turkish knot and the asymmetrical Persian knot. Both knots are tied around two warps. The only way of identifying the knots is by grinning the rugs between a row of knots across the weft. The asymmetrical knot can be tied with the loop on either the right or the left with the tufts coming from the opposite side. Other knots such as Spanish knots, Jufti and Tibetan knots are also frequently used in weaving.